Ucieszyłam się,

kiedy książka Sylwii Chwedorczuk Kowalska.

Ta od Dąbrowskiej, trafiła do mnie jako świąteczny prezent. Wcześniej

czytałam o publikacji w Wysokich obcasach,

więc spodziewałam się czegoś wybitnego. Bardzo szybko jednak cieszyć się

przestałam, a zaczęłam walczyć z materią książki – manierą autorki i stosunkowo

mało ciekawą główną bohaterką. Biografia Anny Kowalskiej Znowu czytam obok.

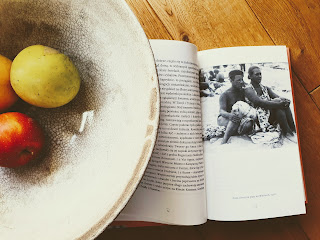

Obok głównego tematu tej książki, a więc lesbijskiego związku Anny Kowalskiej i

Marii Dąbrowskiej. Chociaż książka zaczyna się krótkim wstępem zapowiadającym

burzliwy związek dwóch pisarek, jakoś nie czekałam na ten moment, ani nie był

on dla mnie bulwersujący. Książka zaczyna się nudno – od nastoletnich lat wtedy

jeszcze Anny Chrzanowskiej, urodzonej w 1903 roku we Lwowie. Chwedorczuk

zagłębia się w relacje rodzinne, trudną sytuację materialną rodziny,

poszukiwanie tożsamości u przodków przybyłych z Francji. Anna nie pasuje do

francuskojęzycznej części familii – nie spełnia ich oczekiwań, od przyciężkiego

physis do braku manier i

wyrafinowania. A jednak mieszka z babką i ciotkami w centrum Lwowa. Jako

13-latka beznadziejnie zakochuje się w swojej nauczycielce, Marii Jarosiewicz,

która jednak nie odwzajemnia tego uczucia (i czy do końca zdaje sobie z nego

sprawę, trudno powiedzieć). Kiedy jednak dziewczynka zostaje przyłapana w

dwuznacznej (na owe czasy) sytuacji ze swoją wykładowczynią (kobieta przykłada

dłonie do rozgorączkowanej głowy dziewczynki, a ona zarzuca jej ręce na szyję,

w tym momencie wchodzi pani dyrektor), wraz z końcem semestru zostaje wyrzucona

ze szkoły. Zauroczenie Chrzanowskiej mija. W tej części,

dotyczącej lat młodzieńczych, uderzyły mnie dwie rzeczy – rozgrzebywanie dzienników

Kowalskiej i wiwisekcja jej zapisków oraz podejście autorki do przedstawianych

wydarzeń. Któż z nas nie pisał chmurnych i durnych pamiętników, których pewnie

byśmy się teraz wstydzili. Przegląd niedojrzałych, rozemocjonowanych zapisków

dostajemy tu w pełnej krasie. Kończ Waść, wstydu oszczędź. W podsumowaniu „romansu”

Chwedorczuk pisze natomiast tak: „Zamiast jednak

wesprzeć zagubioną dziewczynkę, dorośli dali sobie prawo do przekroczenia

granic intymności dziecka i bezpardonowo wkroczyli w świat jego uczuć,

tłumacząc sposób, w jaki to zrobili, troską o jego dobro.” (s. 38) Wesprzeć w miłości

do nauczycielki? W 1916 roku? O czym my rozmawiamy? Potem przychodzi

czas studiów, gdzie Kowalska poznaje swojego przyszłego męża, wybitnego filologa

klasycznego i swojego wykładowcę, profesora Jerzego Kowalskiego. Ślub ma

miejsce w 1924 roku. Małżonkowe rozpoczynają wspólne podróże oraz wspólną

twórczość literacką. Jednocześnie w Europie rozpoczyna się zawierucha wojenna,

która znacząco wpłynie na życie bohaterów. W wyniku działań wojennych Polska

traci Lwów, a co za tym idzie, Kowalscy tracą swoje mieszkanie. Pisarki poznały

się w 1940 roku, kiedy Dąbrowska gościła we Lwowie ze swoim partnerem

Stanisławem Stempowskim. Wtedy też Dąbrowska przeżywa zauroczenie Marią Blumenfeldową,

i pisarki nawiązują korespondencję. Rok później Kowalska jest już zaangażowana

uczuciowo. Po wojnie i

mieszkaniu w Warszawie dla Kowalskich nadchodzą lata wrocławskie, a więc epizod

mi najbliższy, jako że związany z moim rodzinnym miastem. Tu zaczęło się robić

naprawdę ciekawie. Jerzy przeprowadza się do stolicy Dolnego Śląska z

początkiem października 1945 roku, Anna miesiąc później. Kowalski jest

zaangażowany w uruchomienie działalności Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. Padają

takie nazwiska jak Władysław Floryan, Stanisław Rospond, Juliusz Krzyżanowski,

Stanisław Mikulski czy Stanisław Kolbuszewski. Kowalscy mieszkają na ulicy

Lindego 10 na Karłowicach. Kowalska angażuje się w organizowanie literackich

czwartków, a w latach 1947-1952 współredaguje „Zeszyty Wrocławskie”. Pod koniec

lat 40-tych mają miejsce dwa ważne wydarzenia w życiu Kowalskiej – w 1946 roku

rodzi córkę Marię, zwaną Tulą, a dwa lata później po ciężkiej chorobie umiera

jej mąż Jerzy. Anna zostaje więc sama z malutkim dzieckiem, w dużym domu, w

bardzo trudnej sytuacji materialnej. O swoim macierzyństwie pisze sucho i

szczerze: „Nie ma chyba na świecie

rzeczy nudniejszej niż (własne) niemowlę. Co za bujda sakramencka z tym

macierzyństwem. To dobre dla baranów. Dziewięćdziesiąt procent lęku i nudy,

reszta szczęście.” (s. 240) W dodatku Maria Dąbrowska szaleje z zazdrości –

pisarka bardzo źle przyjęła wiadomość o ciąży Kowalskiej i nie przepada za jej

córką. Mimo to w 1954 roku Kowalskie przenoszą się do Warszawy, do nowego,

większego mieszkania Dąbrowskiej i rzeczywistoć jeszcze bardziej się

komplikuje. Żadna z pisarek nie czuje się dobrze w nowym układzie i wkrótce

Dąbrowska kupuje dom w Komorowie, gdzie się przenosi. Umiera w 1965 roku. Sama

Kowalska umiera niewiele później, po ciężkiej walce z nowotworem w marcu 1969

roku. Właśnie ostatnie jej przemyślenia i zapiski są najbardziej wstrząsające i

zostają z czytelnikem na długo. „Cierpienie i śmierć. Zwykły ludzki los”, pisze

bez zbędnego dramatyzmu, sucho i rzeczowo (s. 355). Dlatego cieszę się, że

pierwsze 200 stron mnie nie zniechęciło i dotrwałam do końca. Konieczność pisania Zdecydowanie nie

była to najlepsza książka z tych przeczytanych w tym roku. Potwierdza to moje

upodobania – czytanie biografii mnie nudzi i męczy, a przedstawieni ludzie

okazują się być... za nadto ludzcy, niedoskonali, irytujący. Szukam wielkości,

a znajduję człowieczeństwo. To pewnie jest również wielką siłą tej książki.

Znalazłam jednak przesłanie dla siebie, idealne na koniec tego roku, jak i jako

ostrzeżenie i poradę na rok kolejny: „Jak się ciągle nie pisze, to się

przestaje umieć pisać, nawet źle [...]”, zauważa w swoich notatkach Kowalska (s.

244). Więc postanowienie na 2021 – recenzować na bieżąco, a nie gorączkowo

nagdaniać, jak w tym roku. Moja ocena: 5/10. Sylwia

Chwedorczuk, Kowalska. Ta od Dąbrowskiej Wydawnictwo Marginesy Warszawa 2020 Liczba stron: 368 ISBN: 978-83-66500-14-3 I was glad when Sylwia

Chwedorczuk’s book titled Kowalska. The

one from Dąbrowska came to me as a Christmas gift. Earlier I’ve read about

the publication in Wysokie obcasy (a

weekly added to Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper), so I was expecting something

outstanding. However, I stopped rejoicing very quickly, and started to fight

the matter of the book - the manner of the author and the relatively

uninteresting main character. Anna Kowalska's biography I'm reading next to the main

topic again. Apart from the main subject of this book, i.e. the lesbian

relationship of Anna Kowalska and Maria Dąbrowska. Although the book begins

with a short introduction that foreshadows the turbulent relationship between

the two writers, somehow I did not wait for this moment, nor was it outrageous

for me. The book starts boring - from the teenage years of then Anna

Chrzanowska, born in 1903 in Lviv. Chwedorczuk delves into family relations,

the difficult financial situation of the family, and the search for identity

among ancestors who came from France. Anna does not fit into the

French-speaking part of the family - she falls short of their expectations,

from heavy physis to lack of manners

and refinement. And yet she lives with her grandmother and aunts in the center

of Lviv. As a 13-year-old, she hopelessly falls in love with her teacher, Maria

Jarosiewicz, who, however, does not reciprocate this feeling (and whether she

is fully aware of it, it is difficult to say). However, when the girl is caught

in an ambiguous (for those times) situation with her lecturer (the woman puts

her hands to the girl's feverish head and she throws her arms around her neck, at

this point the principal enters), at the end of the semester she is expelled

from school. The love of Chrzanowska dies out.

In this part of the teenage

years, I was struck by two things - digging up Kowalska's journals and

vivisecting her writings, and the author's approach to the events presented.

Who among us did not write gloomy and silly diaries, which we would probably be

ashamed of now. We get an overview of immature, emotional notes here in all its

glory. We could have been spared, as well as Kowalska. In the summary of the ‘romance’,

Chwedorczuk writes as follows: "But instead of supporting

the lost girl, adults gave themselves the right to exceed the limits of the

child's intimacy and ruthlessly entered the world of her feelings, explaining

the way they did it with concern for her welfare." (p. 38) Support in love for the teacher?

In 1916? What are we talking about? Then comes the time of studies,

where Kowalska meets her future husband, an outstanding classical philologist

and her lecturer, professor Jerzy Kowalski. The wedding takes place in 1924.

The married couple begins joint journeys and joint literary work. At the same

time, a turmoil of war begins in Europe, which will significantly affect the

lives of the heroes. As a result of the hostilities, Poland loses Lviv, and

thus the marriage loses their apartment. Anna met acclaimed writer Maria

Dąbrowska in 1940, when the second visited Lviv with her partner Stanisław

Stempowski. It was then that Dąbrowska was infatuated with Maria Blumenfeld,

and the writers started their long-lasting correspondence. A year later,

Kowalska is already emotionally involved.

After the war and living in

Warsaw, the Wroclaw years are coming for the Kowalskis, so the episode is the

closest to me, as it is related to my hometown. Here it started to get really

interesting. Jerzy moves to the capital of Lower Silesia at the beginning of

October 1945, Anna a month later. Kowalski is involved in launching the

activities of the University of Wrocław. There are such names as Władysław

Floryan, Stanisław Rospond, Juliusz Krzyżanowski, Stanisław Mikulski and

Stanisław Kolbuszewski. The Kowalskis live at 10 Lindego Street in Karłowice.

Kowalska is involved in organizing literary Thursdays, and in the years

1947-1952 she co-edits "Zeszyty Wrocławskie". At the end of the

1940s, two important events took place in Anna’s life - in 1946 she gave birth

to a daughter Maria, affectionately called Tula, and two years later, after a

serious illness, her husband Jerzy dies. So Anna is left alone with a small

child, in a big house, in a very difficult financial situation. She writes

dryly and honestly about her motherhood: ‘There is probably nothing more boring

in the world than a (own) baby. What a sacramental nonsense with this

motherhood. It's good for dummies. Ninety percent of fear and boredom, the rest

is happiness’ (p. 240). In addition, Maria Dąbrowska is mad with jealousy - the

writer took the news of Kowalska's pregnancy very badly and does not like Anna’s

daughter very much. Despite this, in 1954, mother and daughter moved to Warsaw,

to a new, larger apartment of Dąbrowska, and the reality became even more

complicated. None of the writers felt comfortable in the new arrangement and

soon Dąbrowska buys a house in Komorów, where she moves. She dies in 1965.

Kowalska herself dies not much later, after a hard struggle with cancer in

March 1969. It is her last thoughts and notes that are the most shocking and

stay with the reader for a long time. “Suffering and death. Ordinary human fate’,

she writes without unnecessary drama, dryly and to the point (p. 355). That's

why I'm glad that the first 200 pages did not discourage me and I made it to

the end. The necessity of writing It was by no means the best book

read this year. This confirms my preferences - reading biographies bores me and

tires me, and the people presented turn out to be... too human, imperfect,

irritating. I am looking for greatness and I am finding humanity. This is

probably also the great strength of this book. However, I found a message for

myself, perfect for the end of this year, as well as a warning and advice for

the next year: ‘If you don't write all the time, you stop being able to write,

even badly [...]’, writes Kowalska in her notes (p. 244). So, the resolution

for 2021 - review on a regular basis, not frantically urge it, as this year.

My grade: 5/10. Author: Sylwia Chwedorczuk Title: Kowalska. The

one from Dąbrowska Publishing House: Marginesy Warsaw 2020 Number of pages: 368 ISBN: 978-83-66500-14-3

czwartek, 31 grudnia 2020

Sylwia Chwedorczuk, Kowalska. Ta od Dąbrowskiej

środa, 30 grudnia 2020

Philip Pullman, The Firework-Maker’s Daughter

Czasami tęsknię za

jakąś książką – przypominam sobie jej fragment i zastanawiam się, co się

dokładnie wydarzyło, przypominam sobie klimat, wyobrażam poszczególne sceny. Tak

właśnie zatęskniłam za trylogią Philipa Pullmana Mroczne materie, którą czytałam podczas studiów (fajne studia,

swoją drogą!). Niestety, nie mam kopii w domu, ale kołatalo mi się w głowie, że

widziałam jeszcze jedną książkę brytyjskiego autora gdzieś u siebie na półce. I

proszę, oto jest! Nietłumaczona na język polski Córka mistrza fajerwerków. Książka – petarda! Perełka Książka jest

niewielka, ale za to niesamowicie pięknie wydana. Krótkiej i prostej fabule

towarzyszą ilustracje Nicka Harrisa. Mistrz fajerwerków, Lalchand, samotnie

wychowuje swoją córkę Lilę, a dziewczynka okazuje się pojętną i utalenotwaną

uczennicą. Ojciec jednak nie widzi jej w zawodzie i pragnie, by znalazła sobie

męża i wiosła życie jak reszta dziewcząt z jej wioski. Lila się na to nie

zgadza. Dzięki swojemu przyjacielowi, Chulakowi, dowiaduje się, że by zostać

mistrzem w swoim fachu musi się udać na górę Merapi, gdzie mieszka duch ognia

Razvani, by zdobyć od niego Królewską Siarkę. Dziewczyna wymyka się więc z domu

i rusza na górę. Nie wie jednak, że jest do tej drogi nieprzygotowana – duchowi

trzeba złożyć trzy dary, a dla własnego bezpieczeństwa zabrać ze sobą wodę z

jeziora Szmaragdowej Bogini. Chulak szybko odkrywa, że Lalchand nie powiedział

mu wszystkiego, i rusza zdobyć dar pani jeziora. Na szczęście nie jest sam –

towarzyszy mu jego niezwykły przyjaciel, gadający biały słoń Hamlet. Chłopiec i

jego towarzysz zdążają w ostatniej chwili i dzięki nim dziewczynka nie płonie,

ale też nie zdobywa magicznego przedmiotu. Hamlet nie jest

zwykłym słoniem – jest słoniem cesarza. Władca używa go, gdy chce kogoś ukarać.

Nieszczęśnik musi wtedy utrzymywać dorodne zwierzę, zapewniać mu jedwabną

pościel i frykasy do jedzenia (a przy okazji bankrutuje i nie stanowi już dla

cesarza zagrożenia). Zniknięcie zwierzęcia wywołuje zrozumiałygniew władcy, a

wszystkie ślady prowadzą do wytwórcy fajerwerków, który zostaje aresztowany. Na

szczęście Chulak, Lila i Hamlet zdążą wrócić, nim mężczyzna zostanie ścięty.

Władca zgadza się oszczędzić jego życie do czasu pojedynku mistrzów sztucznych

ogni, i pod warunkiem, że straszy mężczyzna i jego ambitna córka wygrają ten

konkurs. Zdesperowana dwójka musi walczyć z Niemcem, Włochem i Amerykaninem,

gdzie każde jest mistrzem swojej sztuki. Decyduje natężenie oklasków. Mimo że

przedstawiciele tych trzech nacji zostali pokazani w sposób do bólu

stereotypowy i zamierzony, Pullmanowi udało się oddać orientalnego ducha – gdy

Lalchand i jego córka urządzają swój pokaz, który jest niezwykle subtelny i

ulotny w porównaniu z zaprezentowaną wcześniej kanonadą, publiczność reaguje

pełną kontemplacji i zachwytu ciszą. To właśnie przybysze z zachodniego świata

ratują życie ojca, zaczynając entuzjastycznie bić brawo, i tłum zaczyna

wiwatować. Kiedy impreza

dobiega końca, ojciec i córka mają okazję spokojnie porozmawiać. Okazuje się

wtedy, że Lila miała trzy dary dla bożka ognia – odwagę, wytrwałość i odrobinę

szczęścia. Dostała zatem i dar – Królewską Siarkę – czyli wiedzę i

doświadczenie, które zdobyła w pocie czoła dzięki swojej ciężkiej pracy. Tej książki nie ma

co zestawiać z moimi codziennymi lekturami – to literatura dla dzieci, napisana

z humorem, językiem prostym i dowcipnym. Nie jest za długa, ma sporo ciekawych

i spójnie poprowadzonych wątków pobocznych (wujek Chulaka, Rambashi). Jest

naprawdę sprawnie napisana. Przede wszystkim jednak ma mądre przesłanie. Może

więc Córka mistrza fajerwerków ukaże

się w Polsce? Przecież tytuł mógłby brzmieć bardziej zachęcająco – Petarda! Corgi Yearling Books Londyn 1998 Ilustracje: Nick Harris Liczba stron: 106 ISBN:

978-044-86331-7 Sometimes I miss a book - I

remember a fragment of it and wonder what exactly happened, I remember the

atmosphere, I imagine individual scenes. That's how I missed Philip Pullman's Dark Materials trilogy, which I read

while studying (how cool is that, huh?!). Unfortunately, I do not have a copy

at home, but it was knocking in my head that I saw another book by the British

author somewhere on my shelf. And here it is! Not yet translated into Polish, The Firework-Maker’s Daughter. Book -

firecracker!

Literary jewel The book is small, but

incredibly beautifully published. The short and simple plot is accompanied by

illustrations by Nick Harris. The master of fireworks, Lalchand, raises his

daughter Lila alone, and the girl turns out to be a clever and talented

student. However, her father does not see her in this profession and wants her

to find a husband and lead a life like the rest of the girls in her village.

Lila does not agree to this. Thanks to her friend Chulak, she learns that in order

to become a champion in her trade, she must go to Mount Merapi, where Razvani

the Fire-Fiend lives, to obtain Royal Sulphur from him. So the girl sneaks out

of the house and goes on her quest. She does not know, however, that she is

unprepared for this journey - the demon must be offered three gifts, and for

her own protection she should had taken the water from the lake of the Emerald

Goddess. Chulak quickly discovers that Lalchand hasn't told him everything, and

sets off to get the lake lady's gift. Fortunately, he is not alone -

accompanied by his unusual friend, the talking white elephant Hamlet. The boy

and his companion arrive at the last moment and thanks to them the girl does

not burn, but also does not obtain the magic item. Hamlet is not an ordinary

elephant - he is the emperor's elephant. The ruler uses him when he wants to

punish someone. The unfortunate person must then keep the beautiful animal,

provide him with silk sheets and delicacies to eat (and in this way go bankrupt

and no longer pose a threat to the emperor). The disappearance of the animal

causes an understandable anger of the ruler, and all traces lead to the

firework maker, who is arrested. Fortunately, Chulak, Lila and Hamlet return in

time before the man is beheaded. The ruler agrees to spare Lalchand’s life

until the duel of the fireworks masters, and on the condition that the scared

man and his ambitious daughter win the competition. The desperate two have to

fight against a German, an Italian and an American, each master of their art.

The intensity of applause is decisive. Despite the painfully stereotypical and

deliberate portrayal of these three nations, Pullman has managed to capture the

oriental spirit - when Lalchand and his daughter put on their show, which is

extremely subtle and fleeting compared to the cannonade presented earlier, the

audience responds with contemplation and delight in silence. It is the

newcomers from the western world who save my father's life by applauding

enthusiastically, and the crowd follows.

When the party is over, father

and daughter have a chance to talk quietly. It turns out then that Lila had

three gifts for the Fire-Fiend - courage, persistence and a bit of luck.

Therefore, she was given a gift – Royal Sulphur – which turns out to be knowledge

and experience gained through the sweat of her brow thanks to her hard work.

There is no need to juxtapose

this book with my daily readings - it is children's literature, written with

humor, simple and witty language. It's not too long, it has a lot of

interesting and coherent side stories (Chulak’s uncle, Rambashi). It is really

well written. Above all, however, it has a wise message. So maybe The Firework-Maker’s Daughter will be published

in Poland? After all, the title could sound more inviting - Firecracker! Author: Philip Pullman Title: The Firework-Maker's Daughter Corgi Yearling Books London 1998 Illustrations by Nick Harris Number of pages: 106 ISBN: 978-044-86331-7

Philip Pullman, The

Firework-Maker’s Daughter

Swietłana Aleksijewicz, Czarnobylska modlitwa. Kronika przyszłości (Чернобыльская молитва)

To nie pierwsza

przeczytana przeze mnie książka białoruskiej Noblistki Swietłany Aleksijewicz.

Wcześniej były Ołowiane żołnierzyki

(o wojnie w Afganistanie) i Czasy

Secondhandu (o życiu w Rosji po rozpadzie Związku Radzieckiego). Tamte

książki były jednak w pewnej mierze... przypadkowe. Czarnobylska modlitwa natomiast była wyczekana, i może przeczekana.

Na fali serialu HBO Czarnobyl zaczęłam namiętnie czytać o katastrofie reaktora

na Białorusi. Sięgałam po tą książkę z ogromnymi oczekiwaniami, i chyba trochę

się zawiodłam. Ale po kolei. Katastrofa, która wstrząsnęła Europą 26 kwietnia 1986

roku wybuchł reaktor atomowy w czwartym bloku elektrowni atomowej w Czarnobylu,

powodując potworne skażenie terenu i ewakuację mieszkańców. Początkowo mówiono

ludziom, że będzie to ewakuacja czasowa, ale ludziom nie dane było wrócić do

porzuconego dobytku. To właśnie z osobami bezpośrednio dotkniętymi przez

katastrofę rozmawia Aleksijewicz w 20 lat po wydarzeniu. Zarówno z Ukraińcami, jak

i z Białorusinami. Mimo, że katastrofa miała miejsce na Ukrainie, większość

radioaktywnej chmury przemieściła się w stronę Białorusi, powodując 70%

skażenia terenu tego kraju. Jak gorzko zauważa pisarka, wtedy to właśnie

Białoruś wkroczyła na scenę europejską. Książka zaczyna się

od rozmowy z Ludmiłą Ignatienko, wdową po strażaku Wasiliju, który zmarł na

chorobę popromienną 18 dni po napromieniowaniu, a 14 dni po przewiezieniu do

szpitala w Moskwie. Opowieść wdowy łapie za serce, i jak widać - nie tylko

mnie. Twórcy miniserialu HBO Czarnobyl korzystali z książki Aleksijewicz przy

tworzeniu scenariusza, a wspomnienia Ignatienko w dużej mierze tworzą

dramatyczną siłę tego serialu i są jedną z osi wydarzeń. Aleksijewicz stara

się pokazać awarię reaktora i jej następstwa właśnie poprzez relacje zwykłych

osób, dotkniętych tą tragedią. Pisze: „[...] ja zajmuję się tym, co nazwałabym

historią pomijaną, znikającymi bez śladu śladami naszego przebywania na ziemi i

w czasie. Piszę i kolekcjonuję codzienność – uczuć, myśli, słów” (s.31).

Wybitna dziennikarka kilkakrotnie była w strefie, opisywała zastany tam świat,

zaskoczenie niebezpieczeństwem, krórego nie widać i na które nikt nie był

gotowy. Zdradę człowieka wobec otaczającego go środowiska, samolubną ucieczkę,

zrównanie z ziemią gospodarstw i wsi, zabijanie zwierząt. Ale jej myślą

przewodnią jest: Los to życie

jednego człowieka, historia to życie nas wszystkich. Chcę opowiedzieć historię

w taki sposób, żeby nie stracic z oczy losu pojedynczego człowieka. Los bowiem

sięga dalej niz jakakolwiek idea. (s. 41) W rozdziale Ziemia umarłych daje głos tym, którzy

zostali wbrew zakazowi, albo wrócili do strefy po kilku latach. Również

żołnierzom, którzy zostali wysłani do strefy, by wysiedlać ludzi, orać ziemię,

pilnować porządku. Mieszkańcy nie rozumieli niewidocznego zagrożenia. W rozdziale Korona stworzenia opisuje próby radzenia

sobie ze stratą najbliższych, z narodzinami i śmiercią kalekich dzieci. Opisuje

ludzi, którzy gdzie indziej czuli się naznaczeni piętnem swojej tragedii i

odepchnięci od obawiającego się ich społeczeństwa, którzy wrócili na swoją

ziemię, której ufali, na której się wychowali. „Matka była zadowolona. ‘Zrobiłam

dwadzieścia słoików’. Zaufanie do ziemi... Do wiecznego chłopskiego

doświadczenia... Nawet śmierć syna nie zburzyła im świata, do którego

przywykli...” (s. 136). Opisuje poświęcenie

ludzi, którzy działali przy reaktorze i w strefie. Przewija się wspólny motyw –

przekonanie, że istnieje coś większego od ich życia. Kultuta ofiarności,

ofiary, jak nazywa to Siergiej Wasiliewicz Sobolej, zastępca prezesa zarządu

stowarzyszenia Tarcza dla Czrnobyla. Inni mówią, że człowiek radziecki nie

myśli w kategoriach „ja”, tylko w kategoriach „my”. Zbyt wiele tragedii tępi ostrze dramatu Przeczytałam tą

książkę już parę miesięcy temu, ale odłożyłam notatki i recenzję na później, bo

książka mi się nie podobała. Sądziłam, że może trochę mi się uleży i zmienię o

niej zdanie – ale nie. Czułam narastającą irytację i jednocześnie znudzenie –

historie są do siebie podobne, jakby wszyscy, z którymi rozmawiała

Aleksijewicz, mówili jednym, tym samym głosem. Nawet opowieści dzieci są

rzewne. Jakbym czytała jedną, powtarzaną wielokrotnie opowieść o nadludzkim cierpieniu.

Może na tym polega trudność takiej prozy? Jak oddać emocje, które nie chcą dać

się uwięzić w słowa? Które są większe i straszniejsze niż dostępny język?

Uważam, że tutaj się to nie udało. Choć książka jest poruszająca, a opowadane

historie mają czytelnikiem wstrząsać, to nagromadzenie nieszczęścia powoduje,

że głosy wzajemnie się tłumią i gasną. Natomiast scenarzyści serialu wyciągnęli

z tej prozy co najlepsze i przekuli to w skuteczniejsze medium. Czarnobyl HBO jest naprawdę znakomity. Moja ocena: 5/10. Swietłana

Aleksijewicz, Czarnobylska modlitwa. Kronika przyszłości Wydawnictwo Czarne Wołowiec 2018 Tłumaczenie: Jerzy Czech Liczba stron: 288 ISBN: 978-83-8049-685-9 This is not the first book by the Belarusian Nobel laureate Svetlana

Alexievich that I have read. Earlier, there were Boys in Zinc (about the war in Afghanistan) and Second-hand Time (about life in Russia

after the collapse of the Soviet Union). Those books, however, were to some extent…

random. Chernobyl Prayer, on the other hand, was awaited,

and perhaps waited out. On the wave of the HBO series Chernobyl, I started reading passionately about the reactor

disaster in Belarus. I reached for this book with huge expectations, and I think

I was a bit disappointed. But let’s have a look on the book bit by bit. A catastrophe that shook the

entire Europe On April 26, 1986, a nuclear reactor exploded in the fourth block of the

Chernobyl nuclear power plant, causing terrible contamination of the area and

the evacuation of residents. Initially, people were told that it would be a

temporary evacuation, but the residents were not allowed to return to their

abandoned property. It is with the people directly affected by the catastrophe

that Alexievich talks 20 years after the nuclear catastrophe, both Ukrainians

and Belarusians. Although the disaster took place in Ukraine, most of the

radioactive cloud moved towards Belarus, causing 70% of the contamination of

the country. The book begins with a conversation with Lyudmila Ignatenko, the widow

of Vasily, the fireman, who died of radiation sickness 18 days after

irradiation and 14 days after being transferred to a hospital in Moscow. The

widow's story grabs my heart, and not only me. The makers of the HBO miniseries

Chernobyl used the book by Alexievich

to write the script, and the widow’s statement is one of the opening chapters. Fate goes further than any idea Alexievich tries to show this terrible event precisely through the

accounts of ordinary people affected by this tragedy. She states: “[...] I deal

with what I would call an ignored history, with traces of our presence on earth

and in time disappearing without a trace. I write and collect everyday life -

feelings, thoughts, words ”(p.). The journalist has visited the zone several

times, describing the world she found there, the surprise of the danger that

cannot be seen and for which no one was ready. Man's betrayal of the

surrounding environment, selfish escape, razing farms and villages to the

ground, killing animals. But its keynote is: Fate is the life of one man, history is the life of all of us. I want to

tell the story in such a way as not to lose sight of the fate of an individual.

For fate goes further than any idea. (p. 41) In the first chapter, Land of the

Dead, she gives voice to those who stayed in violation of the ban or

returned to the zone after a few years. Also to the soldiers who were sent to

the zone to displace people, plow the land and keep order. The inhabitants did

not understand the invisible threat, and oftern at the time of harvest, when

people have seen the work of the entire year go to waste. In the chapter The Crown of

Creation she describes attempts to cope with the loss of loved ones, the

birth and death of crippled children. The journalist describes people who,

elsewhere, felt stigmatized by their tragedy and pushed away from the society

that feared them, people who returned to their land, on which they were brought

up. “The mother was pleased. 'I made twenty jars'. Trust in the land ... To the

eternal peasant experience ... Even the death of their son did not destroy the

world to which they were used to... ”(p. 136). Alexievich also describes the dedication of the people who worked at the

reactor and in the zone. There is a common theme - the belief that there is

something greater than their life. The cult of sacrifice, as it is called by

Sergei Vasilievich Sobolej, deputy chairman of the board of the Shield for

Chrnobyl association. Others say that the Soviet man does not think in terms of

"I" but in terms of "we." Too much suffering stifles the

dramatic effect I’ve read this book a few months ago, but put my notes and review aside

for later because I didn't like it and thought I was wrong. I decided that

maybe I would settle for a while and change my mind about it - but no. I felt a

growing irritation and boredom at the same time - the stories are similar, as

if everyone Alexievich interviewed spoke in the same voice. Even the children's

stories are similar and wistful. As if I was reading one, repeated story about

inhuman suffering. Perhaps this is the difficulty of such prose? How to express

emotions that don't want to be trapped in words? Which are bigger and scarier

than the available language? I believe that it has not worked out here.

Although the book is moving, and the stories told are intended to shock the

reader, the accumulation of misfortune causes the stories to mutually suppress

and fade away. On the other hand, the HBO screenwriters took the best out of

this prose and transformed it into a more effective medium. Chernobyl by HBO is really great, easily

the best TV-series I’ve seen this year. My grade: 5/10. Author: Svetlana Alexievich Title: Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of

the Future Publishing House: Wydawnictwo Czarne

Wołowiec 2018 Translation: Jerzy Czech Number of pages: 288 ISBN: 978-83-8049-685-9

poniedziałek, 28 grudnia 2020

John Banville, Prawo do światła (Ancient light)

Banville jest wyjątkowo płodnym pisarzem, do tej pory opublikował 20 książek. Prawo do światła jest trzecim tomem z trylogii The Alexander and Cass Cleave Trilogy, publikowanej w latach 2002-2012. Oczywiście dowiedziałam się o tym dopiero po przeczytaniu książki. Poprzednie dwa tytuły nie są przetłumaczone na język polski.

Diabeł

nie tkwi w fabule

Bohaterem

powieści jest aktor Alexander Cleave, dobiegający już 70-tki. Ku jego

zaskoczeniu zostaje zaproszony do kolejnego przedsięwzięcia, tym razem na

wielkim ekranie, z którego korzysta. Towarzyszy mu młoda gwiazda kina, Dawn

Devonport. Jednocześnie mężczyzna wspomina swoje lata młodzieńcze, kiedy

zakochał się i przeżył romans z 20 lat od siebie starszą matką kolegi, Celią

Gray. 35-letnia wówczas kobieta jest opisana w prozie Banville’a niesamowicie

zmysłowo, a doznania młodego bohatera działają na wszystkie zmysły. Alexander

uprawiał seks z Celią w zrujnowanej chacie w lesie, pełnej zbutwiałych liści,

na skrzypiącej podłodze, w chłodnym potoku nieopodal, w jej starym samochodzie,

w schowku na pranie.

Kiedy nie oddaje

się zmysłowym wspomnieniom, Alexander jest wieloletnim mężem Lydii Mercer i

pogrążonym w żałobie ojcem Catherine, zwanej pieszczotliwie Cass, która

popełniła samobójstwo rzucając się ze skały we Włoszech. Co gorsza, dziewczyna

była wtedy w ciąży. Małżeństwo najgorsze chwile ma już za sobą, ale dalej nie

może pogodzić się ze śmiercią swojego jedynego dziecka i oboje stąpają po kruchym

lodzie. Kiedy Dawn podejmuje nieudaną próbę samobójczą, Alexander zabiera ją ze

sobą do Włoch, by choć przez chwilę móc z nią podróżować jak ze swoją córką, i

zbliżyć się do zagadki śmierci swojego jedynego dziecka.

Zmysłowa

proza

Siła powieści nie

tkwi w fabule, lecz w mistrzostwie języka. Czytając powieść podczas upalnych letnich

wakacji słyszałam wszystkie dźwięki, czułam opisywane przez Banville’a zapachy,

dawałam się uwodzić – za Alexandrem – zmysłowemu obrazowi starszej kochanki. Z

drugiej strony, pisarz zwraca uwagę na ulotność pamięci, przetworzenie swoich

wspomnień przez czas i nagromadzone doświadczenie. Książka zawiera zresztą

swoistą klamrę kompozycyjną – z początku bohater zastanawia się, co się stało z

jego kochanką z lat młodzieńczych, na końcu książki dowiaduje się, że zmarła

zaledwie rok po ich romansie, a oddając się swojemu młodemu i niedoświadczonemu

kochankowi wiedziała już, że jest chora. Dorosły już mężczyzna może się więc

zastanawiać, czy postanowił zlekceważyć pojawiające się objawy, czy też ich

jeszcze nie było, czy jego pamięć postanowiła ich nie zauważać? Taka pogoń za

przeszłością, przesączona przez niezwykle poetycki, zmysłowy język, tworzy

pociągającą i silną mieszankę. Mnie pchnęła do lektury kolejnych książek

Banville’a.

Siła powieści nie

tkwi w fabule, lecz w mistrzostwie języka. Czytając powieść podczas upalnych letnich

wakacji słyszałam wszystkie dźwięki, czułam opisywane przez Banville’a zapachy,

dawałam się uwodzić – za Alexandrem – zmysłowemu obrazowi starszej kochanki. Z

drugiej strony, pisarz zwraca uwagę na ulotność pamięci, przetworzenie swoich

wspomnień przez czas i nagromadzone doświadczenie. Książka zawiera zresztą

swoistą klamrę kompozycyjną – z początku bohater zastanawia się, co się stało z

jego kochanką z lat młodzieńczych, na końcu książki dowiaduje się, że zmarła

zaledwie rok po ich romansie, a oddając się swojemu młodemu i niedoświadczonemu

kochankowi wiedziała już, że jest chora. Dorosły już mężczyzna może się więc

zastanawiać, czy postanowił zlekceważyć pojawiające się objawy, czy też ich

jeszcze nie było, czy jego pamięć postanowiła ich nie zauważać? Taka pogoń za

przeszłością, przesączona przez niezwykle poetycki, zmysłowy język, tworzy

pociągającą i silną mieszankę. Mnie pchnęła do lektury kolejnych książek

Banville’a.

John Banville, Prawo

do światła

Wydawnictwo Świat

Książki

Warszawa 2015

Tłumaczenie:

Jacek Żuławnik

Liczba stron: 302

ISBN:

978-83-7943-544-9

John Banville, Ancient Light

Banville is an exceptionally prolific writer, having published 20 books

to date. Ancient Light is the third

volume in The Alexander and Cass Cleave

Trilogy, published between 2002 and 2012. Of course, I only found out about

this after reading the book. The previous two titles are not translated into

Polish.

The beauty is not in the plot

The hero of the novel is the actor Alexander Cleave, who is already in

his seventies. To his surprise, he is invited to the next venture, this time on

the big screen. He is accompanied by a young movie star, Dawn Devonport. At the

same time, the man remembers his adolescence when he fell in love and had an

affair with his friend's 20 years older mother, Celia Gray. The then

35-year-old woman is described in Banville's prose incredibly sensually, and

the experiences of the young protagonist affect all the senses. Alexander had

sex with Celia in a dilapidated hut in the woods, full of decaying leaves, on a

squeaky floor, in a chilly river nearby, in her old car, in the laundry closet.

The hero of the novel is the actor Alexander Cleave, who is already in

his seventies. To his surprise, he is invited to the next venture, this time on

the big screen. He is accompanied by a young movie star, Dawn Devonport. At the

same time, the man remembers his adolescence when he fell in love and had an

affair with his friend's 20 years older mother, Celia Gray. The then

35-year-old woman is described in Banville's prose incredibly sensually, and

the experiences of the young protagonist affect all the senses. Alexander had

sex with Celia in a dilapidated hut in the woods, full of decaying leaves, on a

squeaky floor, in a chilly river nearby, in her old car, in the laundry closet.

When he doesn't indulge in sensual memories, Alexander is the long-time

husband of Lydia Mercer and the bereaved father of Catherine, affectionately

known as Cass, who committed suicide by throwing herself off a rock in Italy.

Worse, the girl was pregnant at the time. The worst moments are behind the

married couple, but they still cannot come to terms with the death of their

only child and they both tread on thin ice. When Dawn makes an unsuccessful

suicide attempt, Alexander takes her with him to Italy so that he can travel

with her for a while as with his daughter and get closer to the mystery of the

death of his only child.

Highly sensual prose

The strength of the novel lies not in the plot, but in the mastery of

language. While reading the novel during a hot summer vacation, I heard all the

sounds, I felt the smells described by Banville, I was seduced - following

Alexander - by the sensual image of an elderly mistress. On the other hand, the

writer pays attention to the elusiveness of memory, the processing of his

memories through time and accumulated experience. The book contains a peculiar

composition bracket - at first the protagonist wonders what happened to the

lover from his adolescent years, at the end of the book he learns that she died

just a year after their romance, and by giving herself to her young and

inexperienced boy, she already knew that she was sick. So an adult man may

wonder if he decided to ignore the emerging symptoms, if they were not there

yet, or if his memory decided not to notice them? Such a pursuit of the past,

permeated with an extremely poetic, sensual language, creates an alluring and

powerful mixture. It pushed me to read more of Banville books.

The strength of the novel lies not in the plot, but in the mastery of

language. While reading the novel during a hot summer vacation, I heard all the

sounds, I felt the smells described by Banville, I was seduced - following

Alexander - by the sensual image of an elderly mistress. On the other hand, the

writer pays attention to the elusiveness of memory, the processing of his

memories through time and accumulated experience. The book contains a peculiar

composition bracket - at first the protagonist wonders what happened to the

lover from his adolescent years, at the end of the book he learns that she died

just a year after their romance, and by giving herself to her young and

inexperienced boy, she already knew that she was sick. So an adult man may

wonder if he decided to ignore the emerging symptoms, if they were not there

yet, or if his memory decided not to notice them? Such a pursuit of the past,

permeated with an extremely poetic, sensual language, creates an alluring and

powerful mixture. It pushed me to read more of Banville books.

John Banville, Ancient Light

Publishing House: Świat Książki

Warsaw 2015

Translated by: Jacek Żuławnik

Number of pages: 302

ISBN: 978-83-7943-544-9

Mircea Eliade, Młodość stulatka (Tinereţe fără tinereţe)

Odwieczne marzenie o nieprzemijającej młodości

Główny bohater,

profesor Dominik Matei, zostaje uderzony piorunem w Wielkanocny wieczór. Ubranie

się na nim spaliło, a skóra uległa tak dużym poparzeniom, że mężczyznę trudno

rozpoznać, dzięki czemu długo może pozostać anonimowy. Powoli wracają wszystkie

jego umiejętności, odrastają mu zęby i włosy, wbrew logice i biologii staje się

coraz młodszy i sprawniejszy. Jednocześnie jednak cały czas ma dostęp do całego

swojego życiowego doświadczenia, nabytej wiedzy, wyuczonych języków. Zwiększa

się chłonność jego umysłu i możliwości uczenia nowych rzeczy. Daje mu to

możliwość nadrobienia straconego czasu i zmarnowanego życia.

Eliade był

religioznawcą i zasłynął m.in. swoją pracą Sacrum,

mit, historia, gdzie pisze o przeciwstawieniu sacrum i profanum i

gwałtownym wtargnięciu sacrum w sferę

profanum, a więc hierofanii, która

zaburza oba porządki. Takim wydarzeniem w Młodości

stulatka jest moment uderzenia pioruna w Wielkanocny wieczór, a więc w czas

szczególny, czas śmierci i zmartwychwstania Jezusa. Dwie rzeczywistości

przenikają się, a Matei zostaje wtedy obdarzony – wbrew prawom obowiązującym w

świeckim porządku - darem drugiej młodości.

W posłowiu Ireneusz

Kania, wybitny badacz twórczości Eliadego, pisze o podobieństwie opowieści pisarza

do rumuńskiej baśni Młodość bez starości

i życie bez śmierci (Tinereţe fără bătrînete si uiata fără de moarte).

W wielu mitach i legendach bohater odradza się, powracając do miejsca swojego

urodzenia. Tu jest odwrotnie – baśniowy królewicz wyrusza na poszukiwanie

krainy wiecznej młodości, ale gdy przypomina sobie o swoich rodzicach i

królestwie, postanawia tam powrócić. W ten sposób sprowadza na siebie zgubę –

starość i śmierć. Podobnie jest w Młodości

stulatka – profesor po wielu podróżach powraca do swojego rodzinnego

miasteczka, Piatra Neamţ, i idzie do swojej

ulubionej kawiarni, Selectu. Tam czas wraca niemal do momentu wypadku, tym

razem wydarzenia dzieją się niewiele przed Bożym Narodzeniem, 20 grudnia 1938

roku. Profesor zna wydarzenia z przyszłości, bieg drugiej wojny światowej, ale

jego znajomi są zaskoczeni i biorą go za szaleńca. Znika jego młodzieńczy

wygląd, a Matei starzeje się w ekspresowym tempie i umiera po wyjściu z

kawiarni. Jego rodzime miasteczko okazało się być jego pułapką i końcem.

Sama powieść nie

zachwyciła mnie szczególnie. Mimo swoich niewielkich rozmiarów i stosunkowo

licznych fotosów z filmu była dość ciężka w odbiorze ze względu na przenikanie

się wspomnień i obecnych wydarzeń i brak jedności fabularnej. To pewnie

zamierzone działanie, pokazujące współistnienie tych porządków, jednak

czytelnikowi nieco utrudnia życia. Książka wydaje się też emocjonalnie

sztuczna, pozbawiona ciepła, przeintelektualizowana i przechylona w stronę

nostalgii. Nie wiem czemu, ale może wzmianka o Bożym Narodzeniu i zasypanym

śniegiem odległym opustoszałym miasteczku przypominała mi nieco swoim nastrojem

twórczość Dickensa („Opowieść wigilijną” i „Dzwony za kominem”). Gdyby nie ta

notatka, wkrótce zapomniałabym o jej fabule.

Moja ocena: 4/10.

Mircea Eliade, Młodość

stulatka

Wydawnictwo WAB

Warszawa 2008

Tłumaczenie:

Ireneusz Kania

Liczba stron: 256

ISBN:

978-83-7414-277-9

Mircea Eliade, Youth Without Youth (Tinereţe fără tinereţe)

A small book by a Romanian professor and philosopher entitled Youth Without

Youth tells a story of a 70-year-old man struck by lightning, who regains his

youth thanks to this accident. What will he do with this unexpectedly gained

extra time?

The eternal dream of everlasting

youth

The main character, Professor Dominik Matei, is struck by lightning on

Easter evening. Clothes burned on him and the skin was so badly burned that it

is impossible to recognize him, so he can remain anonymous for quite a while.

All his skills slowly return, his teeth and hair grow back, and against logic

and biology he becomes younger and more agile. At the same time, however, he

has access to his entire life experience, acquired knowledge and learned

languages. His mind is absorbed and his ability to learn new things increases.

It gives him the opportunity to make up for lost time and wasted life.

Eliade was a historian of reliogion and became famous for his research

on sacrum, myth and history, where he writes about the opposition between the

sacred and the profane, and the violent intrusion of the sacred into the sphere

of the profane, i.e. hierophany, which disturbs both orders. Such an event in Youth Without Youth is the moment of

lightning strike on Easter evening, and therefore at a special time, the time

of Jesus' death and resurrection. Two realities interpenetrate, and Matei is

then endowed - against the laws of the secular order - with the gift of a

second youth.

In the afterword, Ireneusz Kania, an outstanding researcher of Eliade's

work, writes about the similarity of the writer's story to the Romanian fairy

tale Youth without Old Age and Life without

Death (Tinereţe fără bătrînete si uiata fără de moarte). In many myths and

legends, the hero is reborn, returning to his place of birth. Here it is the

other way around - the fairy-tale prince sets out in search of the land of

eternal youth, but when he remembers about his parents and his kingdom, he

decides to return there. In this way he brings ruin upon himself - old age and

death. It is similar in Youth, a centenarian - after many travels, the

professor returns to his hometown, Piatra Neamţ, and goes to his favorite cafe,

Select. There, time returns almost to the point of the accident, this time the

events take place just before Christmas, on December 20, 1938. The professor

knows the events of the future, the course of the Second World War, but his

friends are surprised and take him for a madman. His youthful appearance

disappears, and Matei is aging at an express pace and dies after leaving the

cafe. His home town turned out to be his trap and brings him death.

The novel itself did not particularly impress me. Despite its small size

and relatively numerous snapshots from the film, it was quite difficult to read

due to the interpenetration of memories and current events and the lack of plot

unity. This is probably a deliberate action, showing the coexistence of these

orders, but it makes life a bit difficult for the reader. The book also seems

emotionally artificial, devoid of warmth, over-intellectualized and tilted

towards nostalgia. I don't know why, but maybe the mention of Christmas and a

snow-covered, remote, deserted town somewhat reminded me of the work of Dickens

(Christmas Carol and A Cricket on the Hearth). Were it not

for this note, I would soon forget the plot.

My rating: 4/10.

Author: Mircea Eliade

Title: Youth Without Youth

Publishing House: WAB

Warsaw 2008

Translated by: Ireneusz Kania

Number of pages: 256

ISBN: 978-83-7414-277-9

wtorek, 22 grudnia 2020

Kelly Barnhill, Syn wiedźmy (The Witch's Boy)

Spokojny, pachnący choinką wieczór, zapalone lampki, atmosfera zimowego wieczoru. Kanapa, ciepły koc, wielki kubek gorącej herbaty. Wreszcie – w ręce prezent dla samej siebie, wydana w ubiegłym roku książka amerykańskiej pisarki Kelly Barnhill Syn wiedźmy. Wielki był mój żal, że oryginalny tytuł książki nie brzmiał Son of a Witch! Ale pewnie literatura młodzieżowa nie może sobie pozwolić na taką... frywolność.

Bracie, gdzie jesteś?

Dwóch siedmiolatków, Ned i Tam, buduje tratwę i spuszcza ją na rzekę, by dopłynąć do morza. Niestety, ich przygoda kończy się tragicznie za najbliższym zakrętem – obaj chłopcy wpadają do wody. Ich ojciec, drwal, jest w stanie wyciągnąć z wody tylko Neda, spuchnięte ciało Tama znaleziono jeszcze tego samego dnia kawałek niżej. Matka, Siostra Wiedźma, nie może się pogodzić ze śmiercią jednego z bliźniąt, oraz z nieuchronnie nadciągającym zgonem drugiego. Łapie więc o zmierzchu duszę Tama i magiczną nicią przyszywa ją do ciała walczącego o życie Neda. Dzięki temu chłopiec pomału wraca do zdrowia, choć za ten zabieg musi zapłacić wysoką cenę. Od tamtej pory słowa nie są mu posłuszne – zaczyna się jąkać i nie jest w stanie czytać.

Jak to było jednak

mozliwe, że matka mogła złapać odchodzącą duszę jednego z braci i przeszczepić

ją swojemu drugiemu umierającemu dziecku? Otóż Siostra Wiedźma jest strażniczką

pradawnej magii, której może używać tylko w dobrym, niesamolubnym celu. Magia jest

bowiem bardzo potężna i zabija tych, którzy myślą tylko o sobie. Jest też

podstępna i może powodować, że zacznie używać swojego strażnika do swoich

celów. Dodatkowo, używanie magii sporo kosztuje. Magia z czasem wykorzystuje

coraz więcej energii od swojego opiekuna. Dlatego właśnie matka Neda, kiedy z

wizytą do ich grodu przybywa leciwa królowa i Siostra Wiedźma musi przyzwać

magię ze swojego odległego domu, po przywróceniu królowej do życia jest

wyczerpana przez niemal dwa tygodnie. Kiedy zostaje wezwana na dwór, by królowa

mogła jej podziękować, zostawia garniec z magią w domu. Na taką okazję czekali

bandyci z sąsiedniego kraju, którzy wiedzą o istnieniu tak potężnej siły i chcą

ją zaprząc do swoich celów.

Tak oto na scenę

wkracza Áine, córka króla bandytów. Dziewczyna wraz z

ojcem po śmierci matki przenosi się znad morza do zaczarowanego lasu i opiekuje

się domem. Ojciec wraca do swojego zbójeckiego zawodu, zbiera swoją bandę

oddanych mu bandytów, a na szyi zawiesza sobie wisior w kształcie oka, który

promieniuje magią. To właśnie ona powoduje, że rudobrody zbój staje się

niezwykle chciwy i zaczyna interesować się starożytną magią z pobliskiego

kraju. Namawia również swojego pysznego i zadufanego w sobie władcę do ataku na

sąsiada, by wejść w posiadanie potężnego artefaktu. Tak oto ścieżki Neda i Áine się przecinają.

Ważne tematy

Barnhill udało się podjąć kilka ważnych tematów pod płaszczykiem baśni dla trochę starszych dzieci. Mamy więc godzenie się ze śmiercią i żałobę – najpierw przy śmierci brata bliźniaka, potem w przypadku śmierci rodziców Aime. Również stara magia, zaklęta w dziewięć głazów, pragnie odejść ze świata, uwolnić się ze swojej kamiennej formy. Śmierć jest tu pokazana jako przejście dalej, wyzwolenie, nowy początek, a nie jako koniec wszystkiego.

Drugi ważny temat

to wolność – magia ma ogromny wpływ

na swoich opiekunów, a korzystanie z niej wiąże się z wysoką ceną. Król

Bandytów całkowicie traci wolną wolę, a magiczny wisior pomału przejmuje nad

nim kontrolę. W końcu mężczyzna zupełnie zapomina, bo jest dla niego ważne, a

kieruje nim już tylko chciwość. Siostra Wiedźma panuje nad magią, ale i ona

zbacza ze ścieżki, ratując swoje dziecko. Odejście magii daje ludziom wolność,

a takze pozwala tak naprawdę odejść tym, którzy umarli już dawno, a ich dusze

zostały zatrzymane na świecie. Wraz z odejściem brata Ned odzyskuje zdolność

mowy i umiejętność czytania, nie ciążą na nim żadne przekazywane z pokolenia na

pokolenie obowiązki. Teraz może zostać kim chce, nie musi już być strażnikiem

magii.

Magię mozna również,

w przypadku Neda, odbierać jako presję społeczną. Dorastamy do życia w

społeczeństwie, dojrzewamy i zostajemy przez nie dostrzeżeni jako

pełnowartościowi jego członkowie, od których wiele się oczekuje. Ned jest

rozdarty przez te słyszane głosy, z których wiele nakazuje mu pójść w różnych

kierunkach. Wiele siły kosztuje go podążenie za własnym głosem, za własnymi

potrzebami i pragnieniami. Chłopiec wykazuje znacznie większą dojrzałość niż

rudobrody bandyta, któremu wizja władzy i bogactw przesłania rodzinę i jej

dobro.

Zaniedbane wątki

Frapujący jest

również wątek wilka. Rozbójnik uczy swoją córkę, że wilki to podstępne

zwierzęta i należy je zabijać, kiedy tylko jest ku temu okazja. Dlatego też

Aime strzela do wilczycy, która gdzieś w lesie ma młode. Na jedno z tych

szczeniąt natyka się Ned podczas swojej ucieczki przez las i wilk zostaje jego

przyjacielem. Dlaczego tak się dzieje? Jakie ma to uzasadnienie fabularne? Nie

wiadomo.

Pewien niewykorzystany potencjał ma również postać zbójcy, którego uleczył Ned. Magia spowodowała, że porwany chłopiec spadł wraz z rozbójnikiem z wysokiego mostu i mężczyzna doznał strasznych, bardzo bolesnych obrażeń. Chłopcu, chronionemu przez magię, nic się nie stało. Strażnik magii podejmuje decyzę, by uleczyć śmiertelnie rannego bandytę i darować mu życie. Mężczyzna jednak nie wyciąga z tego właściwych wniosków – podąża śladem chłopca i będzie się starał odebrać mu magię. To jego strzała, skierowana na Áine, zabije jej ojca. Potem jednak mężczyzna znika, i zawsze żal mi drugoplanowych bohaterów, którzy pojawiają się w książce tylko po to, by wypuścić tą jedną feralną strzałę. Spełnił swoją funkcję, porzućmy go, nie będzie nam juz potrzebny. Podobnych przykładów jest tu wiele.

Jaka jest

największa siła tej książki? Akcja jest wciągająca, a strony czytają się w

zasadzie same. Przysiadałam na chwilę odsapnąć przy świątecznym sprzątaniu, a

budziłam się 50 stron dalej, jakbym wychodziła z innego świata. Naprawdę rzadko

zdarza się, żeby książki czytały się same!

Moja ocena: 7/10.

Kelly Barnhill, Syn

wiedźmy

Wydawnictwo

Literackie

Kraków 2019

Tłumaczenie: Łukasz

Małecki

Liczba stron: 392

ISBN: 978-83-08-06864-9

A quiet evening, the smell of a Christmas tree in the air, lights on,

the atmosphere of a winter evening. A couch, a warm blanket, a huge cup of hot

tea. Finally, a gift for myself, a book by the American writer Kelly Barnhill, The

Witch's Boy, translated to Polish last year. It is my great regret that

the original title of the book was not The Son of a Witch! But probably the youth

literature cannot afford such ... frivolity.

Brother, where are you?

Two seven-year-olds, Ned and Tam, build a raft and set it down on the river to swim to the sea. Unfortunately, their adventure ends tragically around the next bend - both boys fall into the water. Their father, a lumberjack, is only able to get Ned out of the water, Tam's swollen body was found a little further down the river the same day. The mother, Sister Witch, cannot come to terms with the death of one of the twins and the imminent death of the other. So he catches Tam's soul at dusk and sews it with a magic thread to the body of Ned, who is fighting for his life. As a result, the boy slowly recovers, although he has to pay a high price for this procedure. Since then, the words do not obey him - he stutters and is unable to read.

But how was it possible that a mother could catch the departing soul of

one brother and transplant it to her other dying child? Well, Sister Witch is

the guardian of ancient magic, which she can only use for a good, unselfish

purpose. Magic is very powerful and kills those who only think about

themselves. It is also sneaky and can start using its guardian for its

purposes. Plus, using magic costs a lot. With time, magic uses more and more

energy from its guardian. That's why Ned's mother, when the elderly queen

visits their town and Sister Witch has to summon magic from her distant home,

is exhausted for almost two weeks after the queen is brought back to life. When

she is summoned to the court so that the queen can thank her, she leaves the

pot with magic at home. The bandits from a neighboring country who know about

the existence of such a powerful force and want to harness it to their ends

have been waiting for such an opportunity.

This is how Áine, daughter of the bandit king, enters the scene. After

the death of her mother, the girl and her father move from the seaside to the

enchanted forest and take care of the house. The father returns to his rogue

profession, gathers his band of devoted bandits and returns to carrying an

eye-shaped pendant that radiates magic. In this way the red-bearded robber

becomes extremely greedy and interested in ancient magic from a nearby country.

He also persuades his proud and self-righteous ruler to attack his neighbor in

order to obtain such a powerful artifact. This is how Ned and Áine's paths

cross.

Important topics

Barnhill has managed to tackle some important subjects in the disguise of a fairy tale for slightly older children. So we have to accept death and mourning - first the death of a twin brother, then when Áine's parents die. Old magic, enchanted in nine boulders, also wants to leave the world, to free itself from its stone form. Death is shown here as a transition, liberation, new beginning, not the end of everything.

The second important topic is freedom - magic has a huge impact on its

guardians, and using it is associated with a high price. The Bandit King loses

his free will completely, and the magic pendant slowly takes control of him.

After all, a man completely forgets what is important to him, and he is only

driven by greed. Sister Witch controls magic, but she too deviates from the righteous

path, saving her child. The departure of magic gives people freedom, and also

allows those who have long died and their souls to finally go away. With his

brother's departure, Ned regains his ability to speak and read, he is not

burdened with any duties passed down from generation to generation. Now he can

be whoever he wants to be, he doesn't have to be the keeper of magic anymore.

Magic can also, in Ned's case, be perceived as social pressure. We grow

up to live in society, we mature and we are perceived by it as full-fledged

members of whom much is expected. Ned is torn apart by these voices he is

hearing, many of which tell him to go in different directions. It takes a lot

of strength to follow his own voice, his own needs and desires. The boy shows

much more maturity than the red-bearded bandit, who is obscured by the vision

of power and riches which causes suffering in his family.

Neglected threads

However, there are also some neglected threads, that Barnhill tackles,

and then abandons. The topic of the wolf is one of them. The Bandit King

teaches his daughter that wolves are sneaky animals and should be killed

whenever possible. That's why Áine shoots a she-wolf, which has cubs somewhere

in the woods. One of these puppies is encountered by Ned during his escape

through the forest, and the wolf becomes his friend. Why is this happening?

What is the fictional rationale behind this? It is not known.

The robber who was healed by Ned also has an untapped potential. Magic caused the kidnapped boy to fall with the robber from a high bridge and the man suffered terrible, painful injuries. The boy, protected by magic, was fine. The guardian of magic decides to heal a fatally wounded bandit and spare his life. The man, however, does not draw the right conclusions from this - he is following in the boy's footsteps and will try to take his magic from him. It is the bandit’s arrow, aimed at Áine, that will kill her father. But then the man disappears, and I always feel sorry for the secondary characters who appear in the book only to release this one unlucky arrow. It fulfilled its function, let's abandon it, we will no longer need it. There are many similar examples here.

What is the greatest strength of this book? The action is addictive and

the pages basically read by themselves. I used to sit down for a while during

Christmas cleaning, and I would wake up 50 pages away, as if I was coming from

another world. Books are really rare to read themselves!

My grade: 7/10.

Author: Kelly Barnhill

Title: The Witch’s Boy

Literary Publishing House

Krakow 2019

Translation: Łukasz Małecki

Number of pages: 392

ISBN: 978-83-08-06864-9