Po pierwszym nieudanym i niedokończonym spotkaniu z twórczością Marlona Jamesa (nie dałam rady doczytać Krótkiej historii siedmiu zabójstw, poddałam się po 400 stronach) dałam pisarzowi drugą szansę. Okazało się, że bardzo słusznie – od Księgi nocnych kobiet trudno się oderwać. Książka jest kilka razy lepsza niż Kolej podziemna Colemana Whiteheada, którą mi przypominała.

My nie przyszli cię ruchać. My cię przyszli zabić

Większość fabuły toczy się w rozległym

majątku Montpelier, którym zarządza massa Humprey. Akcja dzieję się pod koniec

XVIII i na początku XIX wieku na Jamajce, na plantacji trzciny cukrowej. Młody

panicz Humphrey i jego irlandzki kolega Robert Quinn przejmują zarządzanie

spadkiem po śmierci ojca panicza.

W majątku mieszka wielu

czarnoskórych niewolników, a jednym z nich jest urodzona w 1785 roku Lilit,

owoc gwałtu nadzorcy na jej 13-letniej wówczas matce. Ponieważ ciężarna umiera

przy porodzie, zielonooka dziewczynka trafia na wychowanie do prostytutki Kirke.

Kiedy zaczyna dojrzewać, interesują się nią batowi, a jeden, Parys, w końcu ją

dopada i usiłuje zgwałcić. Przerażona dziewczyna instynktownie się broni i

zabija swojego oprawcę. Schronienia udziela jej starsza służąca z domu

jaśniepaństwa, Homer. Lilit wkrótce zaczyna tam pracę, a młody panicz bardzo

jej się podoba. Nawet dojrzała i realistycznie patrząca Homer ma problem z

utrzymaniem pychy swojej wychowanki w ryzach. Jednak kiedy na horyzoncie pojawia

się piękna i delikatna panna Isobel z sąsiedniego majątku, nadzieje dziewczyny

zostają przekreślone na dobre.

Homer staje się nauczycielką

Lilit, uczy ją liter, mówiąc: „Coś jeszcze ci powiem o czytaniu. Widzisz to? Za

każdym razem jak to otwierasz, jesteś wolna” (s. 70). Dodatkowo kobieta poznaje

młodą służącą z jej siostrami z tego samego ojca i wciąga dziewczynę w

jamajską i karaibską czarną magię. Te umiejętności bardzo się jej przydadzą, gdy w końcu dopadną

ją batowi.

W wyniku wielu perypetii

dziewczyna trafia do majątku rodziców panny Isobel, państwa Roget. Tam uczona

jest dyscypliny i ciężkiej pracy, i znów – żadne cierpienie nie jest jej

oszczędzone. W końcu miarka się przebiera, a jej nienawiść do ciemiężycieli

wybucha z pełną siłą. Lilit staje się narzędziem zemsty, a w wyniku jej działań

majątek znika z powierzchni ziemi. Zawiadomiony o wydarzeniach nadzorca Quinn

zabiera dziewczynę z powrotem do Montpelier, i następuje najbardziej

zaskakująca, niesamowita i piękna część książki. Mężczyzna bierze sobie Lilit

jako nałożnicę, a ona walczy z uczuciem do swojego niegdysiejszego

ciemiężyciela.

Historia Lilit, zaskakująco

silnej i niezależnej niewolnicy, która potrafiła obronić się przed wieloma

niewyobrażalnymi okrucieństwami (chociaż nie wszystkimi, co nadaje tej książce

autentyczności), jest wielowątkowa, skomplikowana i niesamowicie napisana. Głos

dostają czarne kobiety, samo dno niewolniczego systemu, ze swoimi skomplikowanymi

pragnieniami, marzeniami i potrzebami. Książka jest napisana unikatowym

językiem, a tłumaczowi Robertowi Sudół udało się tę unikatowość przekazać

(brawo!). Trzeba się jednak nastawić na dużą dawkę języka, od którego więdną

uszy – „skisła cipa” niech będzie tylko przykładem.

Wszystkie negry chodzą w koło

Głównym tematem książki jest

przedstawione w wielowątkowy, wielopoziomowy sposób niewolnictwo.

Zaczynając od Lilit, która marzy o wyrwaniu się ze swojego beznadziejnego losu

poprzez zostanie kochanką swojego pana, po jej skomplikowany związek z nadzorcą

Quinnem. Robert to ciekawa i wielowymiarowa postać – jest jednocześnie ciepły i

ludzki, sprowadzając dziewczynę do siebie i traktując ją w domu jak równego

sobie człowieka, a jednocześnie sam zaordynował jej ciężkie baty, kiedy Lilit

nie była jeszcze jego nałożnicą. Homer przypomina swojej wychowance historię

Roberta, który na zawsze uciszył zagrażającą jemu i paniczowi Humphreyowi

prostytutkę. Zresztą na jako Irlandczyk ma niższy status społeczny niż jego

brytyjski przyjaciel i pracodawca.

Sami niewolnicy są pokazani na

wiele sposobów. Mamy pewną zażyłość między kobietami, ale nie ma lojalności.

Podobnie jak w całym majątku, dominującym uczuciem jest strach i

pragnienie ocalenia własnego życia, jak i przenikająca wszystko rozpacz

i niepewność.

Księga nocnych kobiet

ocieka okrucieństwem, które aż zatyka dech w piersiach, a opisy są

bardzo ewokatywne. Dulcymena, służąca w majątku Coulibre, kochanka sędziego

pokoju Rogeta (z musu), zostaje okrutnie ukarana za niezamknięcie kóz w

zagrodzie na noc. Zazdrosna żona sędziego, pani Roget, wymierzyła jej karę 166

batów, a opis tej sceny wywiera długotrwałe wrażenie: „Chłoszcze Dulcymenę, jak

najmocniej chłostać potrafi, zamachując się wysoko, razy zadając, aż spod skóry

wyszło mięso, spod mięsa krew” (s. 227). Natomiast jej mąż wykazał się gorszą

od okrucieństwa obojętnością:

Dulcymena już się nie podźwignęła, nawet jak massa przyszedł, kopnął ją dwa razy w bok i raz w cipę, nazywając leniwą krową, co się wyleguje. Lilit próbowała pomóc, ale Dulcymena już nie chciała dla siebie pomocy. W kolejne dni puchła i puchła od takiego mnóstwo ropy i wody, że pękła i skonała. (s. 228)

Homer ma swoje wspomnienia –

pokochała pracowitego Bendżiego i kiedy była wysoko w ciąży oboje zbiegli.

Złapali ich maroni, wolni czarnoskórzy, którzy za odstawianie zbiegłych

pobratymców do właścicieli dostawali finansowe nagrody.

(...) najpierw dali mi lanie. Takie lanie, że mój bąk pierwszy wyzionął ducha i wypadł ze mnie. Dziewuszka. (...) To nie strata bączka mnie dobiła. Ja straciłam samą siebie. Bo te marony tak ze mną postąpiły, jakby żaden czarnuch nie zasługiwał na wolność. Jakby żaden czarnuch nie mógł być człowiek, chłop czy baba. Im się zdaje, że są wolne, ale to podłe nikczemniki i ruchają kozy, to nawet kobiety nie znają. Ja myślałam, że kobieta musi być wolna, żeby być kobieta, a oni mi to odebrali. Odebrali mi kobiecość. (...) Urządzili mi najgorszą chłostę, jaka kiedykolwiek była w Montpelier. (...) Bili mnie batami i konarami i piętnowali za każdy dzień ucieczki. (...) Jak Wilkinsowi skończył się mój grzbiet, kazała mnie piętnować z przodu. Słyszałam ja, jak moje cycki skwierczą jak gęsina na patelni. W nosie czułam swąd własnego palonego mięsa. (s. 247)

Homer naga, skóra napięta na kościach, biodra sterczące, żebra wystające na boki (....). Grzbiet, zad i uda w bliznach wielkich jak pasy na bydlęciu, cycki odrąbane i zarosłe, że tylko sutek świadczy, że urodziła się, by karmić dzieciny. (s. 435)

Jak widać, książka zapewnia sporo

niełatwych emocji, ale napisana jest wartko, akcja jest wiarygodna, a koniec

zapewni nam piękny zaskakujący plot twist. Jedna z lepszych książek, po które

sięgnęłam tego roku. Polecam!

Moja ocena: 9/10.

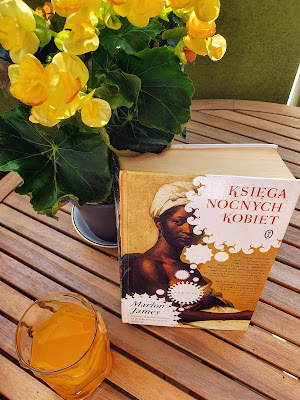

Marlon James, Księga nocnych kobiet

Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków 2017Tłumaczenie: Robert Sudół

Liczba stron: 480

ISBN: 978-83-08-06426-9

After the first unsuccessful and unfinished

meeting with the work of Marlon James (I did not manage to read A Brief

History of Seven Killings, I gave up after 400 pages), I gave the writer a

second chance. It turned out that it was a good decision - it is difficult to tear

oneself away from The Book of Night Women. The book is several times

better than the Coleman Whitehead’s Underground it reminded me of.

We didn't come to fuck you. We came to kill you

Most of the plot takes place in the sprawling

Montpelier estate, which is managed by Massa Humprey. The action takes place at

the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century in Jamaica, on a

sugar cane plantation. Young Lord Humphrey and his Irish colleague Robert Quinn

take over the management of the estate following the death of the Lord's

father.

Many black slaves live on the estate, one of

them being Lilith, born in 1785, the fruit of the supervisor's rape on her

13-year-old mother at the time. As a pregnant woman dies in childbirth, the

green-eyed girl is brought up by a prostitute, Circe. As she begins to mature, Johnny-jumpers

take an interest in her, and one, Paris, eventually grabs hold of her and tries

to rape her. Frightened girl instinctively protects herself and kills her

tormentor. She is sheltered by an elderly maid Homer, a servant at the home of

the noble family. Lilith starts working there soon, and she likes the young

master very much. Even mature and realistic Homer has a problem with keeping her

pupil's pride in check. However, when the beautiful and delicate Miss Isobel

from a neighboring estate appears on the horizon, the girl's hopes are lost for

good.

Homer becomes Lilith's teacher, teaches her the

letters, saying, “Make me tell you something else about reading. You see this?

Every time you open this you get free”(p. 70). Additionally, the woman meets

the young maid with her sisters from the same father and draws the girl into Jamaican

and Caribbean dark magic. These skills will be very useful to her when the Johnny-jumpers

finally get her.

As a result of many vicissitudes, the girl

finds herself in the property of Miss Isobel's parents, the Roget family. There

she is taught discipline and hard work, and again - no suffering is spared her.

Eventually, the happenings in the new place become too much, and her hatred of

its oppressors explodes in full force. Lilith becomes a tool of revenge, and as

a result of her actions, the property disappears from the face of the earth.

Notified of the events, overseer Quinn takes the girl back to Montpelier, and

the most surprising, amazing, and beautiful part of the book follows. The man

takes Lilith as a concubine, and she struggles with affection for her former

oppressor.

The story of Lilith, a surprisingly strong and

independent slave who has been able to defend herself against many unimaginable

atrocities (though not from all of them, which makes this book authentic) is

multi-layered, complex and incredibly written. Black women get a voice, the

very bottom of the slave system, with their complicated desires, dreams and needs.

The book is written in a unique language, and the translator Robert Sudół

managed to convey this uniqueness (bravo!). However, you need to prepare

yourself for a large dose of the ears-withering language - let the

"twisted cunt" be just an example.

Every Negro walk in a circle

The main topic of the book is slavery

presented in a multi-layered, multi-level way. From Lilith, who dreams of

breaking out of her hopeless fate by becoming her master's mistress, to her

complicated relationship with overseer Quinn. Robert is an interesting and

multidimensional character - he is warm and human at the same time, bringing

the girl to himself and treating her at home as an equal human being, and at

the same time he ordered her heavy whips when Lilith was not yet his concubine.

Homer reminds her pupil of the story of Robert who forever silenced a

prostitute who threatened him and Lord Humphrey. Anyway, as an Irishman, he has

a lower social status than his British friend and employer.

The slaves themselves are shown in many ways.

We have a certain intimacy between women, but no loyalty. As in all

possessions, the dominant feeling is fear and the desire to save one's

own life, as well as pervading despair and uncertainty.

The book of the night women drips with

breathtaking cruelty, and the descriptions are very evocative.

Dulcymena, a servant on the Coulibre estate, mistress of the Justice of the

Peace Roget (not out of her free will of course), is cruelly punished for not

keeping the goats locked for the night. The judge's jealous wife, Mrs. Roget,

sentenced her to 166 lashes, and the description of this scene made a

long-lasting impression: "She flogges Dulcymena, she can whip as hard as she

can, swinging high, swinging twice, until meat comes out from under the skin,

blood from under the meat" (p. 227, quote unprecise as translated

backwards from Polish). Her husband, on the other hand, showed indifference

worse than cruelty:

Dulcymena no longer pulled herself up, even as massa came, he kicked her twice in the side and once in the cunt, calling her a lazy cow that lounges. Lilit tried to help, but Dulcymena no longer wanted to help herself. In the days that followed, she swelled and bloated with so much oil and water that she burst and died. (p. 228, quote unprecise as translated backwards from Polish).

Homer has memories of her own - she fell in

love with the hardworking Benji, and when she was well-advanced in her pregnancy,

they both escaped. They were caught by the Maroons, free blacks, who received

financial rewards for returning the fugitives to their owners.

(...) first they spanked me. Such a spanking that my baby gave up first and fell out of me dead. Girlie. (...) It was not the loss that killed me. I lost myself. Cause these maroons acted to me like no nigga deserved freedom. Like no nigga could be a man or a peasant or a woman. They think they are free, but they are vile villains and they fuck goats, they even don't know women. I thought a woman had to be free to be a woman, and they took it from me. They took away my femininity. (...) They gave me the worst flogging ever in Montpelier. (...) They beat me with whips and limbs and stigmatized me for each day of my escape. (...) When Wilkins ran out of my back, she ordered me to be branded at the front. I heard my tits sizzling like goose in a pan. I could smell my own roasted meat in my nose. " (p. 247, quote unprecise as translated backwards from Polish).

When Homer is punished again years later, this time for casting a curse, obeah, the sight of her naked body is terrible:

Homer naked, skin taut on the bones, protruding hips, ribs sticking to the sides (...). Back, rump and thighs in scars as large as stripes on cattle, tits severed and overgrown, that only a nipple testifies that she was born to feed babies. (p. 435)

As you can see, the book provides a lot of

uneasy emotions, but it reads incredibly fast, the action is believable, and

the end will bring a beautiful, surprising plot twist. One of the best books I

have read this year. I highly recommend!

My rating: 9/10.

Author: Marlon JamesTranslation: Robert Sudół

Number of pages: 480

ISBN: 978-83-08-06426-9

Brak komentarzy:

Prześlij komentarz